|

Purcell and Elmslie, Architects

Firm active :: 1907-1921

Minneapolis, Minnesota :: Chicago,

Illinois

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania :: Portland, Oregon |

Navigation ::

Home ::

Grindstone

Navigation ::

Home ::

Grindstone

Ye Older Grindstones

7/4/2006

|

Passageways 3.

Happy Independence Day. Finally got

through the keystrokes for William Gray

Purcell, Part III of the "Preliminary

Draft on 'P & E' Thesis. Thank the extra day of the Fourth of

July holiday weekend. Being a web worker may have similar dynamics to

being sex worker in some ways. When the opportunity to work comes up, it

has to be done right then and there. While I am grateful for the vital, if

not yet sufficient income that arises from doing other web sites, that

means new input here has to slow down in accommodation.

|

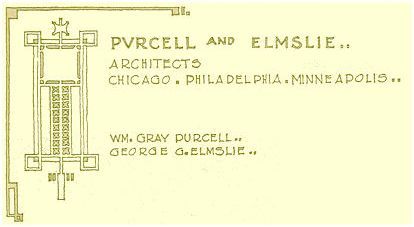

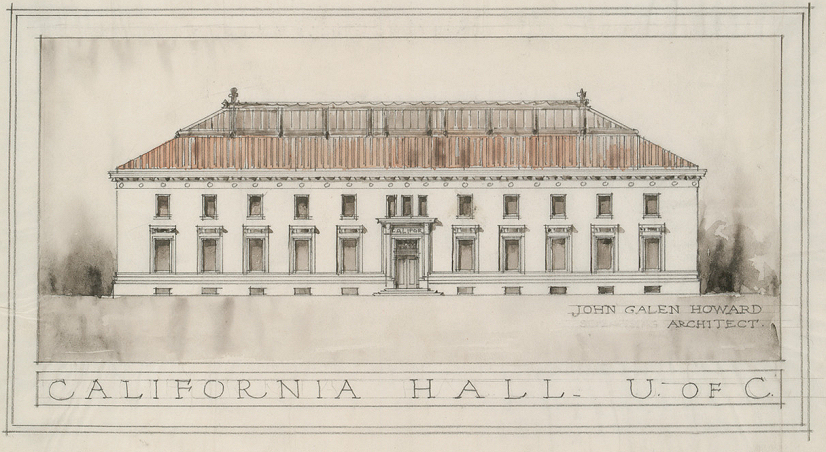

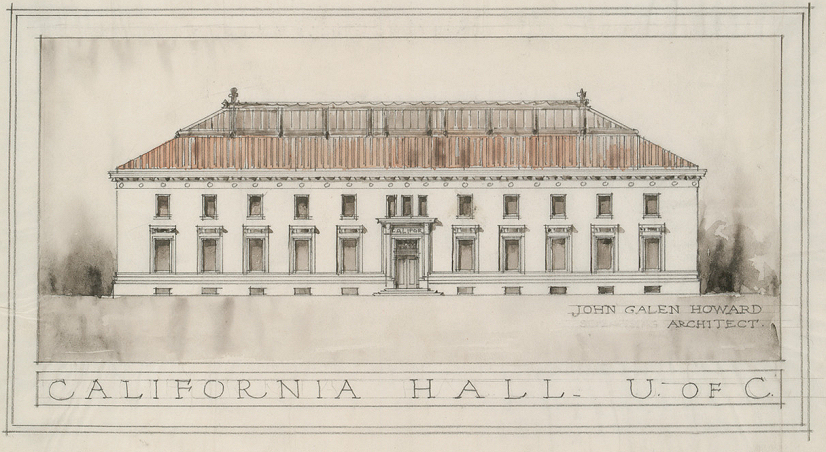

California

Hall, University of California Berkeley

John Galen Howard, architect 1905

William Gray Purcell, Clerk of the Works

Image source: Online Archive of

California |

Purcell continues to pay homage those who

employed him during the two years of his apprenticeship, recollecting in

this chapter his work in the Berkeley office of John Galen Howard. In

doing so, he paints himself into something of a corner. Howard was trained

at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, and had come west from New York after winning

fourth [Purcell says second] prize in the competition sponsored by Phoebe A. Hearst for the

University of California campus at Berkeley. [Those who follow the

machinations of the George Hearst character on Deadwood can easily

appreciate how his wife sought to redeem the family name by supporting the

arts and education as much as she did.]

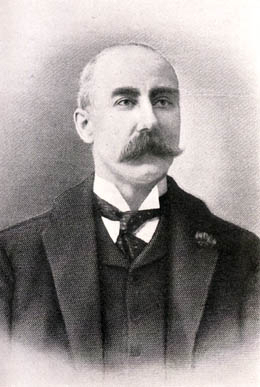

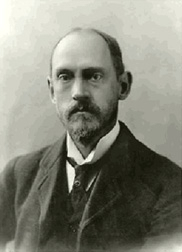

John Galen Howard

Ca. 1900s |

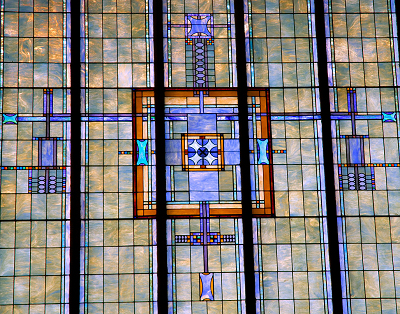

In spring of 1905,

Purcell moved from the Howard office above the old Berkeley post

office to the new atelier in the freshly completed the First National

Bank Building designed by Howard. Images

source: Berkeley Heritage web site. |

First National Bank Building

John Galen Howard, Architect

Berkeley, California 1905 |

After delivering pages of encomium concerning the

character of John Galen Howard, Purcell must then resolve the latterly

revealed history of how Howard, with some apparently brutal tactics, caused the

removal of Bernard Maybeck (1862-1957) from the architectural school

at Berkeley where he had taught since 1894 and was first professor of

architecture from 1898 until being shoved in 1903.

In the end, all Purcell can do is admit that Howard was a

true Bozarter, and his actions have to be viewed in that context. We are

left to consider that Howard believed his way was right and

intended a greater good from what he did. Out, out damned Maybeck!

Maybeck had a good final word when he said, "I've never thought of myself

as an architect. I just like one line better than another." The raw

difference between Bozart ego and the humility of Everyman in organic design is

patently revealed (we'll leave aside FLLW for the purpose of making a

point).

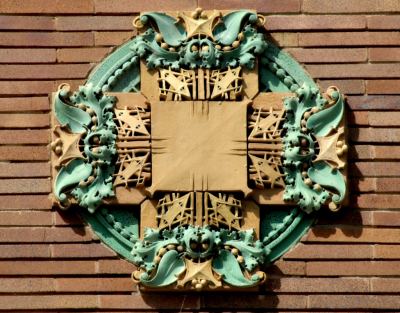

| A more practical

demonstration of the differences between organic design and the

"pastry" of Beaux Art appliqu occurred with construction of the

307 foot high Jane

K. Sather Tower, also known as The Campanile for the housing of a

carillon that has accumulated 61

bells over the years. Designed, or more appropriately said copied

from the tower in Venice, in 1914 and completed three years later, there

was a wee problem. The exterior wall of the tower was granite,

and this had been attached directly to the interior concrete walls of the

structure without consideration that the two materials might have

different expansion coefficients.

Over time in the hot California

sunshine, direct contact between the two elements resulted in

dangerous cracking and flaking of granite shards, which plummeted to

earth or upon the head of the inadvertent pedestrian. The problem

emerged in the 1940s. Purcell published an essay by architect Jacob

Stone in Northwest Architect where the basic materials error

was revealed, despite every effort taken in the design of the steel

framework and foundations to resist earthquake damage.

A PDF of

the article has been created with some demo software (opens a new

browser window for easier return), and it makes for some very

interesting reading. |

Presentation rendering

Jane K. Sather Tower (The Campanile)

John Galen Howard, Architect

University of California Berkeley 1914

Image source: Online Archive of

California |

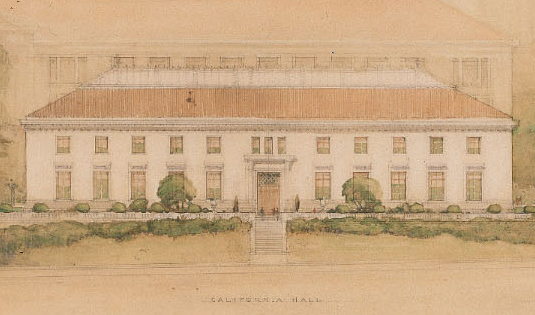

Presentation sketch, possibly

attributable to William Gray Purcell

California Hall,

University of California Berkeley

John Galen Howard, architect 1905

William Gray Purcell, Clerk of the Works

Image source: Online Archive of

California |

An interesting drawing comes to hand through the offering by Online Archive of

California (OAC) of images from the John Galen Howard collection.

Purcell writes that his principal occupation as Clerk of the Works for

California Hall was drawings. One drawing is, by my eye, definitely

lettered by Purcell. Although the format of the drawing is standard issue

Bozart watercolor and pencil technique, the similarity to others from this

period and also those done by Purcell while still at Cornell is plainly

visible. You can just make out that the word "supervising" was erased, as

"Supervising Architect" was the title under which Howard was employed and

his salary paid by Phoebe Hearst.

In the upcoming chapter, after a brief

riff on the "Bay window" phenomenon he saw in San Francisco during his

apprenticeship years, Purcell starts to deal with specific P&E projects in

earnest and discusses the participation of the office staff.

Next up:

William Gray Purcell, Part IV |

7/11/2006

|

Passageways 4.

Continuing our learning curve through

the autobiographical "Preliminary Draft on 'P &

E' Thesis, we come to William Gray

Purcell, Part IV. With the soup and salad of his apprenticeship still

working, Purcell starts placing the meat of the P&E entree on the table.

In this chapter, which was never converted from the third person as

originally generated for David Gebhard, he talks about the demand on Bay

Area architects made by young people seeking a discrete corner in which to

sit closer together -- bay windows with seats, regardless of how the

extrusion of space might disturb the composition of the whole building.

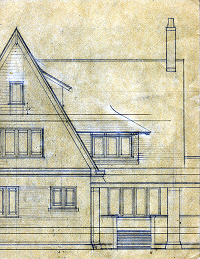

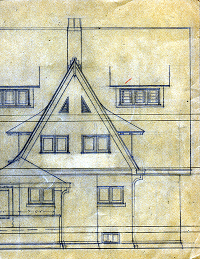

Then we get to an important discussion

about an arc of P&E history, which Purcell described as "a demonstration

of architectural design as a continuity of experience," that resulted many

years down the line in the

Louis Heitman residence. Purcell always loved the

romantic massing of a steep pitched roof. Even from his earliest years as

a designer, he looked for opportunities to use this form. Although he

doesn't mention so here in this draft, there was a house project in

1905, probably more of a sketch for fun than an actual proposed building,

for one Oliver W. Esmond of Berkeley that illustrates perfectly Purcell's

simultaneous fascination and problem.

I have no illustration to offer here of this obscure pencil drawing, which

is large and slightly torn as I recall, but it is a fantasy confection,

more like an infestation, of dormers. Such, in fact Purcell tells us, is

the very core of the issue with this particular approach:

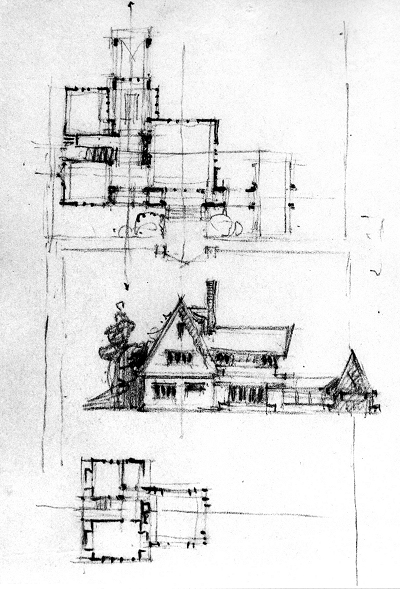

"Purcell kept coming back to this form

in early Catherine Gray studies,

1907 (Purcell and Feick job #4-1/2) but

rejected them. In the Minneapolis climate the idea kept developing snow

pockets. The wedge was plainly tied to rectangular plans with no Ls and

no jogs greater than the width of the broad eaves. Steep roof designs

seemed to get complicated and ultimately wholly out of control too many

dormers." (*)

As I wrote in the

Minnesota 1900 essay:

"For the first time,

Purcell was faced with initiating and sustaining responsibility for the

building process from beginning idea through construction, something that

until then had been only theory for him. A group of four sketches that are

the earliest known drawings for this project provide insight into his

difficulties. He approached the problem from a variety of fronts,

experimenting with the possible compositional effects of a high-pitched or

low-hipped roof treatment. The floor plans of the house evolved more

stubbornly. In the first effort Purcell revealed his lifelong attraction to

the aspiration of a high-pitched roof. The plan, however, would have

none of it. The pitch of the roof subsides quickly across the sequence of

sketches, with two intermediate dormer ideas finally disappearing entirely in

the fourth version."

Purcell recounts the next time he had an

opportunity to pursue the form as being a project for

the

A. D. Hirschfelder residence (Minneapolis, Minnesota

1915). This time the project got to working drawings, but the wife of the

client wasn't buying -- and wasn't giving any leverage, much to the

disappointment of her husband who was all for the game plan.

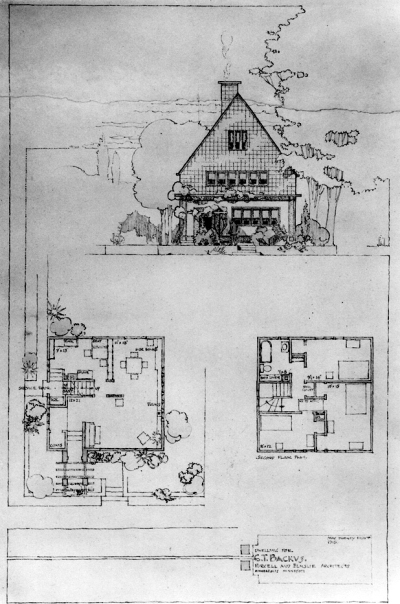

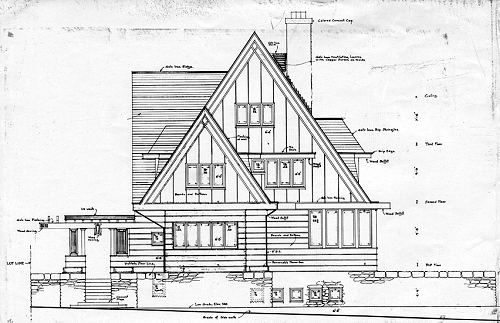

The idea turns up again in the

Charles T. Backus residence (Minneapolis, Minnesota 1915).

According to Purcell in his Parabiographies

entry, Marion Parker and he were responsible for the

design as Elmslie was busy elsewhere at the time. How ironic that the

client gave a total no to the idea, because in his going to Lake Place to

tune Purcell's piano he had fallen in love with the flat roof and other

elements of that design and wanted his own house to be as close as

possible a realization of those lines. Again, Purcell was thwarted.

Then comes opportunity. The first scheme

for the Louis Heitman residence,

as

Purcell recounts, had been shelved because of cost. After an interim

of five years, the Heitmans show up in Minneapolis and are ready to look

again on the notion that they want to move, as sometimes clients do,

right then. Purcell pulls out the canned Hirschfelder drawing set, tips his hand

toward a

steep pitched roof, and with the obligatory "small changes" to

personalize the place for the Heitmans that result in

a completely new set of working drawings, lo, finally, hosanna. The result is a

house that Purcell credits as one of the three most significant ever done

by the firm, right after Lake Place and the

Josephine Crane Bradley residence #2 (Madison, Wisconsin

1914). How important a judgment on his part is that!

Purcell finishes up this

chapter with praise for the foreman who supervised construction,

August Lennartz. Lennartz was with P&E

from 1910 right up through the beginning of World War I. He would have

been the one going to China to supervise building of the

Institutional

Church for Charles O. Alexander,

also known as the Y.M.C.A. project. A few years ago I had the honor to dine

privately at Taliesin with one of the pre-eminent archaeologists in

China, and his wife, a classical scholar who is also a grand-daughter

of one of the last ceremonial empresses of Chinese Imperial court. They

kindly translated the characters on the rendering prepared by P&E:

"In this beautiful place where the

gods themselves would choose to dwell, rises our heavenly temple."

Surely, no doubt, they would. |

|

Institutional Church for Charles O. Alexander, project

also known as "Y.M.C.A"

Siang Tan,

Hunan, China 1916 |

Next up:

William Gray Purcell, Part V

|

7/21/2006

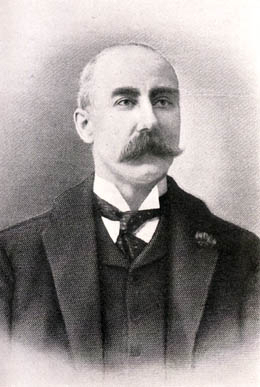

Charles H. Bebb

1856-1942

Image source:

HistoryLink.org |

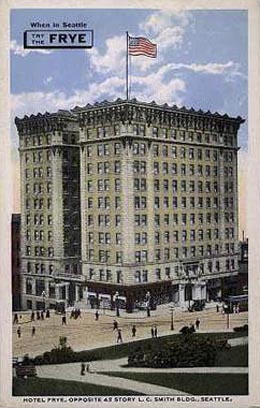

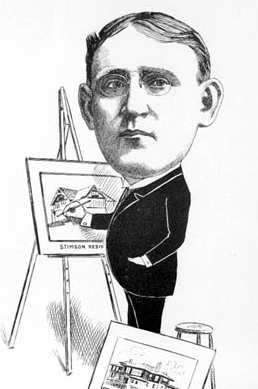

Frye Hotel

Bebb and Mendel, Architects

Seattle, Washington 1911

Image source:

HistoryLink.org |

Louis Mendel

1867-1940

From a cartoon in Argus, ca. 1906

Image source:

HistoryLink.org |

Passageways 5.

In typing our passage through more pages of the "Preliminary Draft on 'P &

E' Thesis, we come to William Gray

Purcell, Part V. Purcell continues taking breath in Berkeley, where we can

conclude with fair certainty is where he caught the tuberculosis that

would, as he describes, "the slow cloud which more than any other factor

was to shape my whole life." Then, even though still wanted at John

Galen Howard's office where he had just overseen the test pits for the

next big campus building, the Library, he determines to move on. Purcell

reports a happy life in Berkeley, but the westering urge was as yet unsatisfied and

required a northern veer to Seattle.

Purcell was there in Washington state

once before, in 1900, on his trip north with his father and brother on an

exciting vacation adventure to the gold fields and Alaska. As he admits,

this environment proved a strange combination of choice and desire for his

own wellbeing. He went west for the warm sunshine, and wound up north in

the chilly rain because that's where he always wanted to be. Bidding adieu

to Walter Ratcliff, Jr., his English-born friend in Howard's office who

wanted to start a business with him, Purcell took a lonely, tossing ship

voyage poleward, sleeping on deck and having "no will to eat." How well

indeed the journey foreshadowed his life experience yet to unfold in that

geographical corner of America just a decade later, ending finally in his

flight back to the sun and the Pottenger Sanatorium in Banning,

California. Pure organic poetry, clef.

A quick stop at the architectural office

of Bebb and Mendel and Purcell got an instant hire from Charles Herbert

Bebb (1856-1942), the now leading Seattle architect who served as

supervising architect for Adler & Sullivan on the Auditorium Building.

Bebb came out to the Pacific Northwest when Adler & Sullivan had prospects

of an opera hall, and following a brief return to Chicago he returned

Seattle to stay after that first siren project evaporated. His partnership

with Louis Mendel (1867-1970) had an age difference with Bebb similar to

that between Purcell and Elmslie, and Bebb and Mendel joined in prosperous

practice from 1901 to 1914. Curiously, the younger Mendel departed to

maintain a small boutique practice, while Bebb went on to scale great

commercial Bozart heights with another partner, Carl F. Gould (1873-1939).

Purcell reports the Bebb and Mendel

office was full of "experts," and he was armed only with his "enthusiasm."

History would prove this as an office intent on the business of

architecture, that is making the architect serious money while cultivating

the mantle of social respect that leads, most likely, to additional

opportunities to make bank, and perhaps bank buildings, over lunch at the right club. Purcell was a

fish out of water. Undoubtedly his reference of service in the

Sullivan office had gotten him in the door, but the opportunity turned out

to offer two weeks to look for another job and leave before "being fired."

That brought him to his stint in the

office of architect A. Warren Gould, with a "fifty percent" raise in the process.

Interestingly, Purcell does not have two words to say about the principal

of the firm, but instead chats up a downtrodden office character he

befriended and sought to rescue. The Seattle residency ended in what might

be considered something of a clever family intervention. Purcell was

enticed to a winter vacation at the Grand Canyon by his doting grandmother

Catherine Gray and her companion Annie Ziegler (a faithful woman who

honored for some thirty years a pledge to W. C. Gray to stay with his widow). The two women went back to Seattle with Purcell, and his father

coincidentally also shows up fretting as usual about his son's health.

As Purcell recounts it here in these pages (and it varies a little

elsewhere in the telling but is essentially the same story), his father

offers a trip to Europe and he packs up, heads toward Chicago under the

umbrella of better weather, and makes for the Konig Albert, a German

steamer about to sail from New York.

Purcell's attraction to the Pacific

Northwest area very likely originated in his idyllic experiences at Island

Lake, where his grandfather was reliving -- right down to the architecture

-- the pioneering life in which he had been raised on the Gray farm in

Ohio in the 1840s. The log cabins and Indians were still within arm's

reach, even if Purcell could only afford to buy an occasional breakfast at

the best restaurant in town. Much of Purcell's life was spent in emulation

of his grandfather, and his descendent quest for the ideal life he

experienced as a child at the family camp in northern Wisconsin always

required trees and water.

In the next section Purcell takes us

along on his year long travels with George Feick, Jr., in Europe and the

Near East.

Next up:

William Gray Purcell, Part VI |

research courtesy mark hammons

research courtesy mark hammons

![]() research courtesy mark hammons

research courtesy mark hammons