|

|

|

Purcell and Elmslie, Architects Firm active :: 1907-1921

Minneapolis, Minnesota :: Chicago,

Illinois |

Ye Older Grindstones

2/27/2005

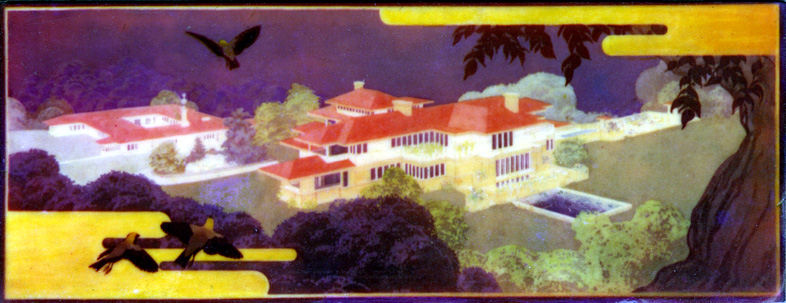

Charles O. Alexander residence, project

Purcell and Elmslie

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 1915

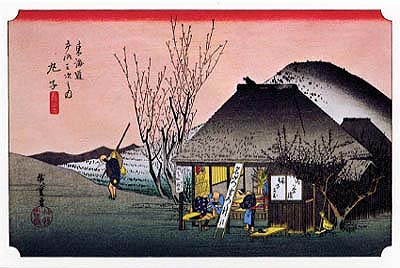

Hess-Ives separation process color photograph of rendering by John W. NortionLiving Color. According to the log analyzer, there are 65-75 regular readers of this blog. A few hundred a month tune for whatever reason, which could be just a google-bot anomaly. Comments have been consistent with regard to the recent red or blue state Hiroshige prints in the previous Grind, so I think we know pretty much the political inclination of those interested in P&E. Little niceties continue to evolve, most recently the request to put up larger images for the Grind as--all too true--I don't always have the time to get around to making enlarged view pages. But the feedback has been awesome, and there are now about a hundred new slides waiting to be scanned of buildings that have few or no images to date. Speaking of images, my thoughts over the past couple of weeks have dwelt some on the journey of William Gray Purcell alongside the development of photography. Purcell received his first camera, a Kodak "Brownie," when he was eight years old as a gift from his grandfather W. C. Gray. The camera had not yet been released to the market, and Dr. Gray had been given one to review for The Interior. That launched Purcell on a seventy-five year long unquenchable interest in the medium. In addition to recording his own life as a matter of course (and for which we can thank him), WGP also happened to be present at a private demonstration of one of the very first color motion pictures during 1918 in Philadelphia. He experimented with all the forms of photography he could find, including tintypes, glass negatives, and Lumière autochromes, as well as trying out the various papers and printing techniques.

Henry B. Babson Residence

Louis Sullivan and George Grant Elmslie, architects

Riverside, Illinois [demolished]

Perspective view from street

Lumiere autochrome, 1914

William Gray Purcell, photographerCharles A. Purcell Residence #1

Purcell and Feick

River Forest, Illinois 1909

Side elevation

Lumiere autochrome, 1914

William Gray Purcell, photographerEdward L. Powers Residence

Purcell, Feick and Elmslie

Minneapolis, Minnesota 1910

For example, the nine or so surviving color images taken of P&E buildings during 1914 were his handiwork. Purcell tried the Hess-Ives process for color photography, which involved the separate exposure of three plates which were then illuminated together to create a color image. He seems to have preferred the Lumiere process, since only a couple Hess-Ives images remain, and the truly wonderful autochromes are more numerous. However, any statement that judges the documentation remaining of the pre-1919 period must always contend with the year when the Purcell household belongings were lost in a train wreck while on the way to Oregon. Purcell mentioned the extent of this personal catastrophe in terms of correspondence with John Jager, for example, and we know that the first copy of "Nils the Gooseboy" perished in the same accident. Larger, less fragile works, such as Lawton Parker's portrait of Dr. Gray and the "Chicago River" oil by Albert Fleury were recovered, albeit both canvases suffering significant damage. Hess-Ives separation process image

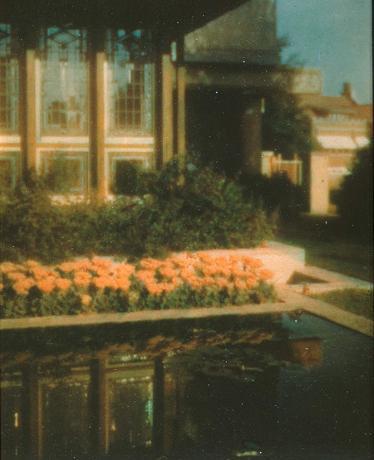

Edna S. Purcell Residence

also known as Lake Place

Purcell and Elmslie

Minneapolis, Minnesota 1913Notice how the pool is filled completely to the rim. Purcell lauded this effect as one of the firm's best accomplishments in water features. Alas, the restored pool at the house now lacks this nicety.

Main banking room, 1914

Autochrome Lumiere, by William Gray PurcellMerchants National Bank

Purcell, Feick, and Elmslie

Winona, Minnesota 1912

Original skylight, 1914

Autochrome Lumiere, by William Gray PurcellMerchants National Bank

Purcell, Feick, and Elmslie

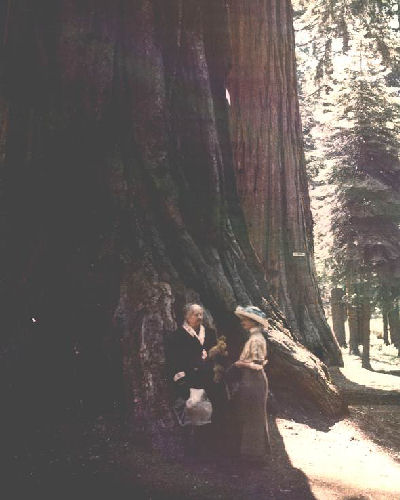

Winona, Minnesota 1912His hobby could also get him in to trouble. During the rough financial years of 1920-1928, Purcell had periods of difficult cash flow. While his millionaire father bailed him out again and again, the roller coaster ride effect on his family life was trying, to say the least. His wife Edna, raised with a certain standard of living, might not know from week to week whether she would have a cook or a maid. Yet adopted son James Purcell told me in a phone conversation in the 1980s that WGP would not infrequently toddle in through the door with the latest and greatest camera gear. We can only guess if the noisy rows that erupted were any part of his growing interest in long treks into the forest with brushes, oils, and canvas. Certainly the number of photographs seems to fall off considerably, with the exception of his 1928 trip to Europe, of which there are hundreds. The image to the right is actually from the 1910s, taken during the trip the whole family took to see Yosemite and the great Sequoias. Pity the two woman forced by Purcell to stand so close together for the sake of a photograph. Read the body language. Such Victorian principle on the left with Grandmother Gray ("she's William's wife, there for I must bear it"), and Edna Purcell ("I'll stand here but I am not going to look.") Note that neither of the two adopted boys are in sight.

Catherine Garns Gray and Edna Summy Purcell

Lumiere autochrome, 1915

William Gray Purcell, photographerCuriously, there are no color photographs remaining in the Purcell Papers of the Portland era; that I have seen anyway. Records exist that talk about certain family albums created by Purcell that included color images and which were given to James, who probably passed them on to his descendants. However, my inquiries with the family have turned up no such albums. A few other trails are still to be trod, however, so perhaps these will yet show up. [As an aside, Purcell wrote appreciatively of a mahogany photograph keepsake box for Edna Purcell made by Robert Pelton at the same time that craftsman made the Lake Place floor lamp. The family had no knowledge of this object, and for perhaps fifteen years I believed it likely lost. However, much to my surprise I discovered it had rested since 1961 in the hands of Arthur Dyson, Purcell's last apprentice. While mishandling by David Gebhard, who borrowed it from Art, resulted in the box being placed in the Purcell Papers after his death--Art wants to get it back--it is still holding photographs, mostly those given by Purcell while Art worked for him.]

Keepsake box for Edna S. Purcell

Cuban mahogany 1913

Ralph B. Pelton, craftsmanWhile the fact is little known today, Purcell was the producer of what was possibly the first true architectural history film (WGP thought so), all in living color. Since his Portland days WGP had befriended Erven, the son of his photographer friend Alda Jourdan. Erven went on to become a professional photographer and lived in southern California at the same time Purcell resided at "Westwinds" in Monrovia. Purcell lent Jourdan money to buy cameras and equipment, for example, to get his studio up and running in Los Angeles. In 1946, Jourdan spent several months shooting "Southern California Houses of Frank Lloyd Wright," which showed the Hollyhock, Storer, and Ennis houses, among others. WGP wrote (lengthy) didactic panels that scrolled past, but little voice narration made when the architectural was on screen. As a reviewer of the time noted, "this film is smart enough to let the architecture speak for itself." With a soundtrack composed by Ernst Gold, who would later win an Academy Award for the theme from Exodus, the film aired on the local public television station in Los Angeles and a copy was dispatched to Taliesin West for the passing glance of FLLW. Next up: Chromographs, being the final gift in return from Purcell for the art of photography

2/19/2005

Which state are you in?

Dust to dust. My best intention of a weekly update disappeared beneath a flu-like visitation that caused me to also miss some hours at the day job. During such Kobiashi Maru times, when the needs of the body outweigh the needs of the mind, or the bank account, there is little to do beyond contemplate the intermittent nature of awareness--and thus the variable nature of contemplation itself. In some measure, Buddhist practice allowable by modern Western circumstances to a lay person has a simple sounding antidote to achieve stabilization, being the regular (read: stable) practice of meditation. Two years ago my friends got together and sent me to a retreat in Colorado at Shambhala Mountain Center, where I learned how to meditate. The wisdom is easy to learn; the skill of practice has been harder to come by.

Unless, of course, the work I do with this web site can be counted as a form of meditation. Something very akin to realization comes, perhaps intermittently like the flu, but on the whole I can see reflected in these pages a kind of stabilization through what has been a long, hard, often dark, and most certainly confused journey. Call it the meditation of life. I contemplate the life of P&E and thereby gain perspective on my own. I always did this, but less skillfully at first--and for many years I shied away from obvious understandings out of self-doubt. Was I projecting, only, through the misstep of transference? Was I ever going to be certain enough what I knew about them, and therefore of myself, to write with conclusive authority? Very recently the answer came to me in words remembered from the meditation master who gifted me two years ago as I sat on a cushion, struggling to breathe at an altitude of 7,500 feet in the Rocky Mountains. "If you are thinking about meditating, you are not meditating." That's a root principle.

Thinking and doing are two separate acts. The failure to bridge the gap is the difference between potential and actual effect. John Jager, for example, had great potential. Yet, in the end, the vast majority of his intellectual endeavor was deliberately consigned to the flames of extinction by the instruction of his wife, Selma, who survived him, at her own death in 1974. The scarce remains of his lifetime of studies--and the research library on which they were based--of Etruscan, Chinese, and Japanese culture, not to mention his wide ranging thoughts on architecture and philosophy, now languish dispersed, fragmented, incomplete, hidden without propagation in a few thousand letters, notes, and glosses in the Purcell Papers; and possibly, if they survived the destruction of Yugoslavia, a dusty collection of manuscripts and personal journals forgotten at some archives in Ljubljana.

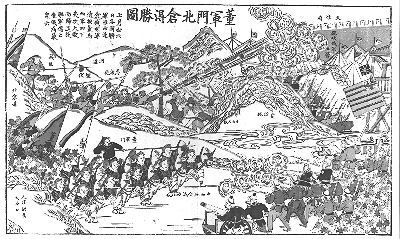

Chinese political street poster (b&w photograph), 1901

Collected in Beijing by John Jager

The original woodblock print is in color.

Source: William Gray Purcell Papers

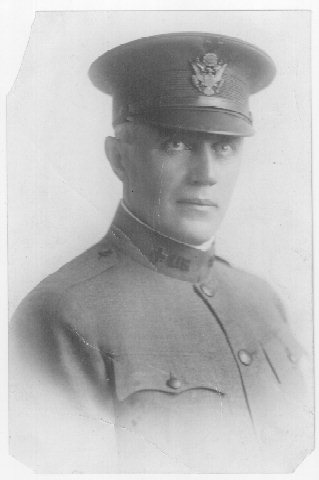

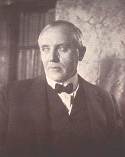

John Jager, in his American Red Cross uniform as he served in his native Serbia during World War I. 1918

Source: Minneapolis History Collection

Elevation and floor plan

St. Bernard's Catholic Church

John Jager, architect

St. Paul, Minnesota

Source: The Western Architect, October 1908 (10:10)True, Jager made contributions of merit. His church of St. Bernard's in St. Paul still serves the blue collar parish for which it was erected, as do other of his few built structures in Minnesota. His great, huge painting of the Minneapolis public train and trolley system created for the St. Louis Exposition of 1904 is lovingly preserved by the Minneapolis Public Library. For fifteen years, Jager dutifully took the streetcar up Hennepin and then University Avenues to the Bruce Publishing Company in St. Paul carrying the manuscripts, illustrations, and draft layouts for Purcell's long running organic soapbox in Northwest Architect. Yet today what student or scholar reading "What the Engineer Thinks," a statement of organic principle published in the July, 1915 [Volume XXII, #1] issue of The Western Architect showcasing the work of Purcell and Elmslie, would know without prompting that the putative author, "E. van Regay," is a pseudonym for John Jager? The man given the honorific of "silent partner in P&E" by Purcell remained true to the sobriquet until he died. This fate for a man who started off his studies at the Vienna Polytechnicum in the 1890s while Otto Wagner was in full sway, then was the architect sent by the imperial government to rebuild the Austrian Legation in Bejing following the Boxer Rebellion in 1901 and took copious and invaluable photographs, as well picked up the odd but now extremely rare political handbill, along the way? A man who wandered Japan for over a year at the turn of the last century collecting an enormous hoard of high quality

ukiyo-e a nd superb Samurai sword hilts, experiencing first hand and at length the same persuasive cultural energy that was so compelling an influence on Frank Lloyd Wright? A man who was the first and for a good while the only man in Minnesota who could perform the calculations necessary to work in cast concrete, and who was a major participant in the development of the 1905 Minneapolis City Plan? And just when did he give up his own practice and go to work for the very "corporate" Hewitt & Brown?This picture is fluff, I know, but so flavorful-->

Opium, anyone? Heroic, indeed. NOT!

Thank you, no, I'll just have a spot of tea.

The Heroic Defense of the English Legation in Beijing by Fritz Neumann

Source: Cowles Archives

St. Mark's Cathedral

Hewitt & Brown, architects

Minneapolis, Minnesota 1910

Interior woodwork detailing by John Jager

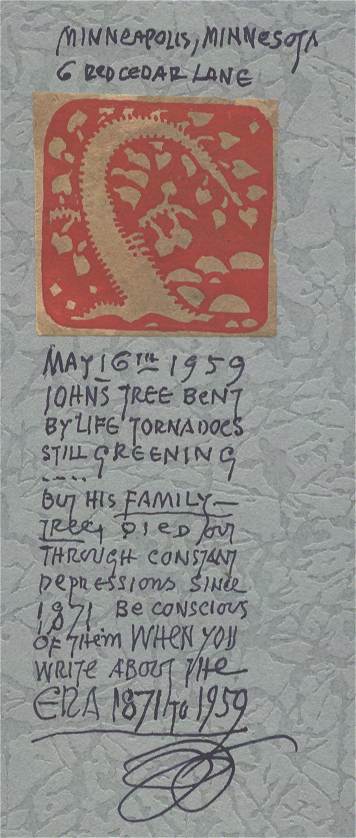

Compare the overt Secessionist quality of St. Bernard's with this traditional piece of Norman Revivalism.While Jager was off in his native Serbia during World War I, that City Plan was set aside when Daniel Burnham came to Minnesota in the 1920s and proposed to drive a Bozart stake through the heart of town to the McKim, Mead, and White-designed Minneapolis Institute of Art [MIA]. After being laid off at the beginning of the Great Depression from his longstanding job as librarian/archivist for Hewitt & Brown, he watched anonymously as his historic collection of fine Japanese prints, sold in financial desperation to his former employer in a lump, were donated to MIA where the only record of their provenance says "Gift of Edward Hewitt." His finely wrought gullywumping cabin property in northern Minnesota at Vermillion Lake was consumed by the collapse of the stock market only a year after Purcell and he spent one last vacation there in 1928 (the last time they would physically see one another). His house, along with his precious trees on Red Cedar Lane near Minnehaha Creek in south Minneapolis, would have also been lost but Purcell stepped in and paid off the mortgage. The few renderings left from his schooling in Vienna were salted away behind an interior lath and plaster wall of his basement, come to light only through the recent remodeling by a later owner. And, as mentioned, his manuscript and photographs, and everything else not already moved beyond the pale, were scorched to ash as if to remove any last trace.

Jager's company in Serbia, 1918. Jager is second from the left.

Source: Minneapolis History Collection

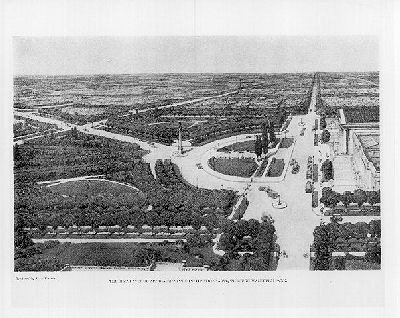

Aerial view rendering of the Minneapolis Institute of Art and the proposed boulevard linking the museum to downtown Minneapolis in the City Beautiful Plan of 1918

Source: Minneapolis History CollectionIn my best Dracula voice: "Such fine arteries..think of the places we can go together, my dear, if you would only give up all your former history...just a little pain in that neck of the neighborhood and the transition will be over soon enough..."

Or my best pirate voice: "Arrrr. Ye've seen the cursed drawing...remember, dead neighborhood communities tell no tales..."

The organic nature of expression is inescapable, most especially to those whose feet are held closest to the fire. Yet, I have often observed the nature of unconscious awareness, if it that phrase isn't taken as an oxymoron, at work in this state of affairs. If I had to choose a single expression by John Jager to fulfill the "as above, so below" dictum of reflex-ion/reflection at the heart of organic understanding, it is easy to snap right off the best example. In the 1920s, Jager reported with glee in a letter to Purcell that he had spent his entire summer alone at Lake Vermillion (Selma stayed in town and sometimes lived separately from Jager even then) excavating a long trench to build a perfectly joined and level sunken stone pathway on his property that had no other function than to be without origin and destination. He then buried the works and restored the native landscape. This, he chuckled to Purcell, was his gift of mystery to some unknown future archaeologist who would undoubtedly perplexed by the apparently missing places of beginning and end. The accomplishment seems to me, however, to be the perfect metaphor of his own life passage. Who will ever know unless by happenstance on the way to somewhere else?

Portrait by Purcell

(1923)

Jager residence

Red Cedar Lane

Minneapolis, Minnesota

(circa 1940s)Possibly that is a little cruel, as he reminds me in an annotation--made scarcely a few weeks from his death-- from the back of a three ring binder that for many years held a P&E manuscript intended for publication by the University of Minnesota Press--but that never happened (left). The fact is that he spent much effort that came to naught. He remained a prisoner of self-doubt, unwilling to present his studies to public criticism through publication. Reading his annotations on Purcell's documents, for example, one can perceive his sensitivity to poetic nature, particularly to irony. But his insights were internalized into frustrations and disappointments in whose embrace his potential for intellectual communication was eventually smothered. There is a wonderful line in the movie "Amadeus," where Mozart is berated for lacking discipline in writing down his music. "It's no good to anyone if it doesn't get out of your noodle," he is told in so many words. On the other hand, his ministrations toward the records from the various Purcell practices, undertaken resolutely from 1930 until his death in 1959. were devoted and loving. All interested parties owe much to his refusal to throw things away as instructed when Purcell deemed them "inconsequential." A colleague during the 1980s, when we were together processing the Purcell Papers, remarked with disdain that Jager had "defaced" many important documents with his "scratching," notations very like in form to those adjacent here. But Jager did almost always marked a handling date, usually when got he first received a record and possibly another again when he again pried the document back away from Purcell in California.

ASHSB trademark logo, designed by JagerIn beginning this Grind, I philosophized that the difference between possibility and result is the connection of action. Some conditions attach. Actions must be skillful, timely, and effective if not necessarily efficient. Most all, they must be in-formed. Gathering information is a stage of process in creating a product, the way certain types of Tantra are described: a stage of generation and a stage of completion. Just as some flower buds wither unopened from the branch, so are human pursuits. Here in Los Angeles there are armies of scarcely conscious, wholly untrained, utterly insensitive "gardeners" who descend on the foliage weekly with machetes at their sides and leaf blowers on their backs. I mention that only to note one can get whacked down by the unfortunate conditions of life in general, like the two year old but lush avocado tree by my patio which was removed last week because the "gardeners" were asked by the apartment manager to weed the area. Being blindly disappointed with someone, even irate, is an impediment to wisdom. You can never know the true circumstances without inquiry. Still, the tree was nice as long as it lasted.