|

|

|

Purcell and Elmslie, Architects Firm active :: 1907-1921

Minneapolis, Minnesota :: Chicago,

Illinois |

Ye Older Grindstones

6/30/2003

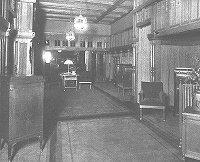

Interior, first floor looking toward street

Edison Shop

Detroit, Michigan

Niedecken and Wallbridge, interior designers

Interior, second floor looking toward elevator

Interior, second floor looking toward streetWhat might, should, could have been. The phonograph was to the 1910s what DVD is to the 2000s. Everyone who had even the slightest bit of disposable income opted for this new entertainment product. A vast number of these machines were purveyed by the interstate merchantile concern owned by Henry B. Babson and his brother, Fred. Henry was a longtime client of Louis Sullivan, of course, but he followed Elmslie for his continuing architecture needs when GGE departed the Auditorium tower. Purcell and Elmslie built Edison Shops--usually alterations of existing buildings--in Chicago, Illinois, Kansas City, Missouri, Minneapolis, Minnesota, and San Francisco, California. The furniture and fixtures for these shops were mostly, if indeed not all, manufactured by the premiere firm of Niedecken and Wallbridge [N&W], interior designers and furniture makers located in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. This is old news. Less well known, however, is the Edison Shop in Detroit done by N&W without the benefit of Elmslie at the drafting table; images for this location have been added to the N&W Team page. Built after the P&E shops were finished, there is an interesting warp of the "corporate" image that Elmslie crafted, and the effort by N&W to create a more "traditional" environment. In part, this is clearly to reconcile the cabinetry styles of the product with the architecture of the sales room, a proverbial sore thumb for P&E. Elmslie tried to cure the problem at an entirely different level, by designing instrument panel covers.

No doubt the Detroit shop was under the direction of Fred Babson, who did not share his brother's affinity for Progressive forms. Fred, in fact, made sure that the contract for the New York store was given out while his brother was in Europe, thus depriving P&E of a smart Fifth Avenue location and all the prestige that implied. Purcell notes this loss in a Parabiographies entry. By the by, Henry Babson gained great fame as a thoroughbred Arabian importer/breeder with all the time at the track such a thing connotes. His daughter, Elizabeth Babson Tieken, continued the family occupation, and only quite recently passed away (February, 2002) after a long and much lauded life with the pony crowd. One last note about Henry Babson, one that shows a kind heart--despite his unfortunate decisions in the 1920s that eventually led to the death knell of the Riverside house. Very late in Elmslie's life (1949), when the aged and irritable architect was in declining health and largely dependent on his sisters for support, Henry Babson came over one afternoon, asked some innocuous "consultation" questions, and dropped a nice check on the table when he left--for auld lang syne, as related by Purcell.

6/27/2003

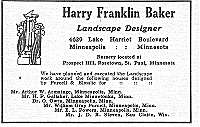

Advertisement from The Western Architect

Henry B. Babson residence, landscaping

Jens Jensen, landscape architectAddenda. A few minutes only tonight. Put up image of an ad by P&E landscape designer Harry Franklin Baker and linked his page to the jobs he is known to have worked on. In Illinois, landscape architect William [Wilhelm] Miller worked on at least one P&E commission, the Amy Hamilton Hunter residence (Flossmoor, Illinois 1916); and of course Jens Jensen worked with Elmslie on the design for the Henry B. Babson residence, landscaping (Riverside, Illinois 1914).

6/25/2003

Sketch for leaded glass panel insert

George W. Stricker residence, alterations

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Dining room panels

A. W. Armitage residence, alterations

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Tulip and rose transom panels

A. W. Armitage residence, alterations

Leaded glass panel in "The Smoker,"

Charles A. Purcell residence #1 (River Forest, IllinoisDebris. Through the intermediary hands of John Jager and Fred Strauel, as well as his own willfulness, Purcell spent several decades editing the contents of the records that survived from the P&E office. In particular, he removed drawings of "inconsequential" or "insignificant" works, mostly consisting of alterations to pre-existing structures. South Minneapolis, particularly the Kenwood district, contains the (largely unknown) remaining results of a number of these kinds of commissions; most of the documentation, however, vanished from the Purcell Papers with the cleansing by Purcell. These alterations usually consisted of adding enrichments such as leaded glass panels, stencils, sawed wood panels, and light fixtures. A few added structural elements like a porch. One or two were important enough to Purcell's sense of poetry to retain some of the records, such as the George Stricker residence alterations in which Purcell introduced a bi-plane (the Parabiographies entry is revealing). This panel was removed from the house in 1994 and sold to the Minneapolis Institute of Art, but numerous other panels, mostly plainer but characteristic of the basic P&E "thread" motif, remain in situ. The Stricker alterations evolved through the process of the client working toward the design of an entire house, but lacking the money to follow through and in the end having to content themselves with further alterations to their existing home. Other clients liked their old hearth enough, but wanted a bit of sprucing up. The A. W. Armitage residence alterations are an example of Purcell at work as an ornamentalist in the Purcell and Feick partnership, with the barest hint of what will be when Elmslie arrives later on. It is interesting to compare Purcell's early glass in the Charles A. Purcell residence #1 (River Forest, Illinois), which was designed at the same time as the Armitage panels.

6/23/2003

Lake of the Isles,

Minneapolis, circa 1910s

<--

Cast iron remains of the entrance light fixture, Madison State Bank-->

Leuthold residence stencil board

Knee deep in minutiae. Added scans for another of The Architectural Record articles on The Prairie School Exchange: Ferre, Barr. What is Architecture? Vol I, #2 [October-December, 1891], pp. 199-210. One reason I get distracted and even forgetful about things is balky equipment. Now the scanner and associated software are acting up. So I repair that, sort of, and then must divert to find something actionable in the time remaining today. I pick up miscellaneous things that have been in the "To Do" queue(s). Housecleaning, as distinct from housekeeping. Scraps, flotsam, but interesting! Added three views of Lake of the Isles taken by Purcell in the 1910s, when the idyllic nature of the then bucolic neighborhood where five P&E houses took eventual root was still relatively isolated, not like today--overcrowded with houses and people variously walking, rollerblading, or cruising in their cars, not to mention the seasonal flotillas of canoes puttering hither and yon. Put up two ghostly images of the Madison State Bank light standards, such as they survive. By the time the bank was demolished (thus removing any architectural incentive to visit this small town), these stands had been thrown unceremoniously into the backyard of a greenhouse, where they rusted in the Minnesota winters for a long while before being rescued in time for pseudo-restoration and display at the "Prairie School Architecture in Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin" exhibit in 1982. Lastly, I brush up against some photographs of original stencil boards used in the decoration of many P&E interiors; the sample test here was used for the John Leuthold residence. I don't have identifications for all of them, unfortunately, and there are enough that sorting and putting them up is going to take--guess what?--more time!