|

|

|

Purcell and Elmslie, Architects Firm active :: 1907-1921

Minneapolis, Minnesota :: Chicago,

Illinois |

Ye Older Grindstones

John Jager in a photograph taken by Purcell in 1923 Doorway to "The Cave," Red Cedar Lane Those who came before. From the 1930s until 1959, the body of records known as the Purcell and Elmslie Archives (most properly described as a record group within the William Gray Purcell Papers) were cared for by John Jager (1871‑1959). An architect whose early training came from the Vienna Polytechnicum during the 1890s, Jager was sometimes referred to as "the silent partner" of P&E. This honorific arose out of his long friendship (1908-1959) with Purcell and their shared explorations of organic thought over a half century, rather than any direct contribution to the work of the firm. Jager did publish an essay called "What the Engineer Thinks" under the reversed name pseudonym of "E Van Regay" in one of The Western Architect issues (July, 1915), but his most significant and lasting efforts occurred in the basement of his house on Red Cedar Lane in south Minneapolis. In a space known as "the Cave," Jager ordered, inventoried, annotated, and studied the records of P&E from 1934 until his death. The documents remained in the same flat files in which they were transferred to the University of Minnesota by the late 1960s-early 1970s, just before Jager's widow Selma died.

George Elmslie possessed a cavalier attitude toward the drawings and office records of his practices. He threw out, for example, the magnificent presentation renderings for the Australian Parliament Buildings Competition and left document cases of other large drawings in the Chicago winter weather on his back porch--all turned to mush. He also destroyed Sullivan's diaries, all of this to Purcell's recriminating distress and Jager's everlasting horror. In truth, however, Purcell was no better in some ways. Remember always when consulting the Purcell Papers that, however abundant the documentation, you have a remnant deliberately edited by Purcell over decades of currying the desired perspective. Living at his Pasadena estate and reviewing the P&E records in Minneapolis by remote inventory, Purcell frequently ordered Jager to destroy drawings that he felt were "inconsequential" or "incidental," and therefore distracting from the "real" accomplishment. Sometimes--but not always--Jager disobeyed, leaving an annotation on the document in question to record his refusal for the appreciative eyes of posterity. Eventually for this and other reasons--mostly having to do with Purcell sending students and researchers, such as David Gebhard, to the Cave and Jager feeling at least unappreciated and possibly threatened--relations between Purcell and Jager soured toward the end in an atmosphere of possessiveness and suspicion.

Amazing how some things stick in your mind when other, vastly more important ones, evaporate with time. During those long departed years of the late 1970s-early 1980s when, blessedly, I joined the ongoing effort of Barb Bezat (and Alan Lathrop) to bring overall order to the Purcell Papers, she once picked up a document annotated by Jager and made a terribly damning comment about how he had defaced the entire collection with his marks. Jager developed a little triangular glyph or "chop," if you will, that recorded the date when something was inventoried or otherwise handled. True enough, these are on many, many letters and manuscripts. But they are part of the story and, I think, deserve a share of respect. [I sometimes see photocopies from the Purcell collection with my own little bracketed annotations and sorely wish I had not been naive and untrained enough to make such a mistake.] Jager may have owed the roof over his head to Purcell, who had paid off the mortgage in the 1930s when Jager lost everything in the Crash AND got laid off from his records keeper/librarian job with Hewitt & Brown, but he also never wavered from thirty years of daily effort in the Cause.

Annotation by John Jager, the first P&E archivist, about his research method, still true even now in the electronic age A cenotaph, of sorts, to the way of things This all comes to mind because of my present attempt to plow through all the boxes of research materials that have accumulated around me for over twenty years. There are still several left to go, but recent research requests from users of this site sent me scurrying through sixteen bookcase SHELVES of three ring binders. Some of these belonged to Jager, and were discarded from the Purcell Papers in the removal of offending containers whose metallic rust and adhesive off-gassing taint documents. In the back of one, I found two annotations by Jager whose images shown above. Timely comments, which I post here for their human touch.

Today I sorted out the format for extended Jager pages, added his portrait, and also got up the skeleton of the bibliography for the Elmslie writings. Also revised the home page to add a section on archival references, to get up some of the scope and content notes about the Purcell Papers which, although available as part of the on-line finding aid to the collection elsewhere on Organica.org, are useful in their own right here. Most importantly, I have at long last added the much needed acknowledgements page. Still inventorying and ordering the work plan of the future. I both rejoice and despair at the amount waiting for attention, and the uncertain motion of it all.

5/8/2003

Learning to see organically. My astrologers, tarot readers, and psychics assured me that May was going to be a difficult month to move things, not least because Mercury is retrograde (and transited the sun, no less, yesterday. See the cool pictures at NASA). Since my earlier little epiphany about what I am DOING with this site, several things have presented themselves which were formerly present but largely unseen--or at least unrecognized or unarticulated. One was the central thesis in a nutshell: "Integrity is the basis of organic action."

Strange how the everyday events of life can bring home such pith. I record the following event here not because it relates to P&E in any direct way, but as a revelation that highlights an underlying commonality about living such as P&E reflected in their architecture. Theirs was the architecture of democratic life, one which in every way meant to exalt the progress of social respect (hence, the alternative label for them as Progressives). As regular readers of The Grindstone know, means for survival have been scarce of late years around this keyboard. Today an acquaintance who also has shared lamentations of financial distress announced that he had subcontracted $2000 of work out elsewhere that could have been done better and faster in my own household. His project is a set of playing cards, a la the Iraqi Most Wanted deck, of Hollywood celebrities who criticized the recent war. Each individual was sketched and applied to the card with a "humorous" comment that essentially belittled their political convictions by denigrating their intelligence or some personal characteristic.

When I was shown this project, which is now at the printers, my first reaction was a kind of sorrow. My spirit was horrified, even though I was told the decks were intended "just to make money off the conservatives." When the $2000 artwork commission was mentioned, however, right away my poverty consciousness came to the fore. I got frothy for about two hours, offended that my roommate friend who does graphics hadn't even been called to bid on the work. Then, like a gentle stroke from heaven, the realization dawned on me that my first impression of the merchandise was the correct one--and for all that two grand would have lifted this establishment up out of the gutter, I was heartened not to be involved. What came to me was this: 132 American service men and women gave their lives for that military exercise, and regardless of the hidden political and corporate motivations of those who sent them off to die, their sacrifice was ostensibly to ensure that people like me can sit here and say what we feel and believe. That even includes my acquaintance and his shameful deck of playing cards.

For me, there is an intense irony: Pandering to the lowest denominator of political bias, those cards are actually an insult to those who died so that those opposed to war could continue to speak their beliefs IN FREEDOM. That means with respect. There isn't a shred of respect in the deck there. What a complicated and ambiguous world we live in. And so did P&E. Purcell once wrote that he and his colleagues were considered subversive "reds" for their social views by the conservatives of the time. Kind of gives a new twist to the idea of a house of cards.

5/1/2003

Charles Wiethoff house

Courtesy Tim Loftus

Catherine Gray house

Courtesy Tim Loftus

E. C. Tillotson house

Courtesy Tim Loftus

C. T. Bachus house

Courtesy Tim Loftus

Tim Loftus, the goodly proprietor of the PrairieStyles web site, has kindly granted permission to link his P&E images to this site. This is a sweet bonus for visitors here, since his images are a nearly decade newer than any of mine. I don't even have color photographs of the Wiethoff and Tillotson houses, either. Like my own web exhibit, PrairieStyles is obviously a labor of love, something offered as a shared interest, even passion, for scholarship in the achievements of organic design by that movement called, by some who came later, the Prairie School. Tim covers many other Progressive architects, and provides excellently written biographies and commentary. Thank you, Tim!By the by, the best dissection of the origin of that term "Prairie School" can be found in chapter one of H. Allen Brooks' seminal Frank Lloyd Wright and His Midwestern Contemporaries; anyone reading this site probably already owns or has at least checked out a copy of that inescapably important book. In going through a host of storage boxes lately, I found my oldest paperback copy, long since fallen apart into individual pages, with about a hundred yellow Post-It notes attached from well over 15 years ago. I was truly amused to see what issue I had taken with some of Brooks' statements. What a difference time can make. Not to say that I don't still find some of my questioning insights valid; I just have mellowed tremendously with the evaporation of being a Young Turk. Turk I may still be with my interpretations of spiritual philosophy behind organic architecture, but young I no longer am by the calendar date.

All of which brings me to a decision, something of a conclusion, about what I am doing here to further my particular perspective on P&E and organic philosophy. I set out the basic poem in several essays (published in French, Italian, and English) and the Art and Life on the Upper Mississippi: Minnesota 1900 monograph that appeared in 1994. I've been doodling, so to speak, an outline to a fuller book, but the distance of my present residence from the native field of discovery (I live in LA) and the Purcell Papers at the University of Minnesota presents quite an impediment to the kind of research I feel necessary. Additionally, I have developed a strong aversion to the hassle of traveling. Also, while there are at least two publishers who would gladly review my manuscript for publication, I don't have the financial resources to produce one. So, instead, I have resolved to write what I can and publish it on this web site.

This approach leaves me free to supply extensive facsimile documentation, unlimited illustrations, and basically get everything out as I finish individual sections without having to wait for the all-or-nothing publication pipeline. I can also annotate things more fully, with anecdotal asides and other sorts of things that would never appear in an academic tome. When I am as done as I am destined to get, perhaps that can form the basis for a publication. Until then, this is my forum, my soap box, my hobby horse. To get things running, I created a starter page, In the Spirit of Democracy, which first off contains my best little effort to date to articulate the essential philosophical understanding (at least from my point of view) behind the organic gnosis.

4/28/2003

Side table

Edward Decker residence

T. B. Keith dining set

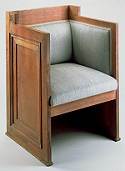

Babson chair

Merchants Bank chairStill on my furniture kick. Added a link to the one piece of P&E furniture held by the Minnesota Historical Society, a small side table from the demolished Edward W. Decker summer residence at Lake Minnetonka. There's a strange--but not bad--story behind the acquisition of this table, but one perhaps better left unreported. Suffice to say that the table wasn't always in this museum collection, and how it got there was a curious bit of provenance, at least the part to which I was privy back in the mid-1980s. I suppose one reason I am disinclined to repeat the tale here is my flickering memory of those years, and I'd rather not walk on that Minnesota ice.

The majority of P&E furniture in museum collections can be found in the galleries of the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Probably no other institution is as deserving, considering what they spent--and continue to spend--on maintaining Lake Place as part of their permanent collection. Furniture, particularly chairs, has accumulated from the Decker house, Merchants National Bank (they have TWO!), the Henry B. Babson residence sleeping porch remodel (last time I sat in this chair--in 1981--it had a bright orange, very 1970s fabric for upholstery), and the phenomenal T. B. Keith dining room set. The Chicago Institute of Art has the Babson "Grandchildren's" Tall Clock.

Also added a view of some leaded glass from the Madison State Bank, and a module of polychrome terracotta from the Farmers and Merchants State Bank (Hector, Minnesota). There's another one of these in the Purcell collection at the University of Minnesota, and a few more are floating about in private hands. These modules were dislodged--like other ones before them in the Owatonna bank--during a 1970 remodeling, and some were thoughtfully distributed to worthy institutions by the conscientious bank president. During the wonderful Prairie School exhibition held in the St. Paul Landmark Center in the early 1980s, these disembodied examples were collected and lined up for a real visual treat in the galleries.

4/27/2003

Master bedroom suite, with doubled twin beds and dresser, as used in Catherine Gray house Double bed, vanity, chair, and bench, shown in Catherine Gray house; also used in Lake Place Potluck today, as I take a few moments from the heavy press of the freelance. A few images herewith of some bedroom furniture designed by Purcell in 1908, and thereby hangs a tale. Purcell was essentially raised by his maternal grandparents, Willliam Cunningham Gray and Catherine Garns Gray [CGG]. W. C. Gray died in 1901, and CGG hung out more or less alone for five years in their Oak Park house. In 1906, however, she decided that the place was too big (and, no doubt, too full of memories). After a stint of staying with Garns relatives in Pennsylvania, she accepted the invitation of her grandson to come live in his new house just built on then suburban Lake of the Isles in south Minneapolis. All the high Victorian furnishings of the Oak Park house were dutifully installed in what was originally called the "W. G. Purcell residence," a circumstance that P&E found often hurt the success of their interiors. Clients had heirlooms and favorite pieces that did not cohabit comfortably with the up-to-the-moment poetry of their new P&E houses. Nonetheless, Purcell designed some bedroom furniture for this house, and it was images of these pieces that fetched up recently out of a box.

Purcell got hitched in 1908, and surely he must have thought that the two most important women in his life would get along. Rude awakening occurred almost immediately, and William and Edna Purcell took an apartment in the nearby Kenwood district until 1913, when their new residence was finished on Lake Place just across the alley from where Catherine Gray remained, with all her heavy furniture, in the original house. That's why the first house is now known as the Catherine Gray house, and the second the Edna S. Purcell house. Equal deference to the ladies on Purcell's part. No question that Catherine, on the lakefront, got the better picture window, but Edna scored with the unparalleled decorations of her own. Besides, there was a fine view (at the time) of the lake from her back porch. At least one of these bedroom sets, the painted one, wound up as furniture in the Lake Place bedroom (originally for guests, but later for son James after they adopted). The Purcells used brass beds for themselves, on rollers to make the short trip onto the sleeping porch. As for whatever happened to the dark-stained bedroom set, there is no record. It's out there somewhere, floating in the Twilight Zone with the E. L. Powers dining room table, the furniture for the various Edison Shops, and what Purcell called "a multitude" of fern stands, desks, and incidental tables produced by the firm.

Where, indeed, did it all go? It can't have all been discarded. The Decker dining room table, for example, turned up at the Minneapolis Society for the Blind (as it was then called), being used for paint projects.